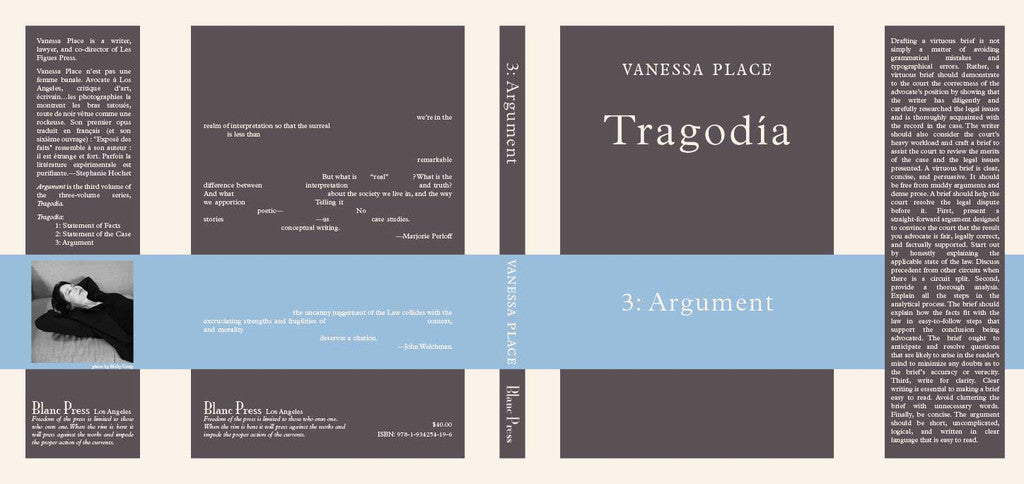

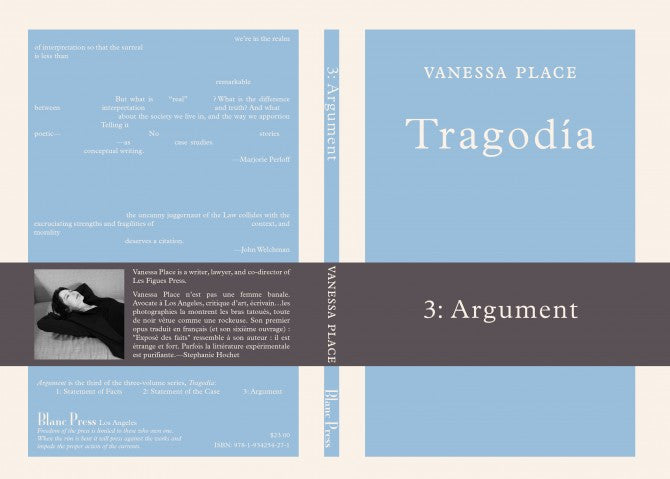

Tragodía: Argument

Tragodía: Argument

Vanessa Place

Couldn't load pickup availability

Hardcover, with dustjacket, 298 pages

Blanc Press, September 2011

ISBN-13: 978-1-934254-19-6

Dimensions: 6.25 x 9.5 x 1 inches

Tragodía 3: Argument by Vanessa Place is the third volume of Place’s three-volume series, Tragodía.

Tragodía is composed of the three parts of an appellate brief: Statement of Facts, which sets forth, in narrative form, the evidence of the crime as presented at trial; Statement of the Case, which sets forth the procedural history of the case; and Argument, which are the claims of error and (for the defense) the arguments for reversing the judgment. Place’s Statement of the Case project involves reproducing Statements of the Case from some of her appellate briefs and representing them as poetry.

Drafting a virtuous brief is not simply a matter of avoiding grammatical mistakes and typographical errors. Rather, a virtuous brief should demonstrate to the court the correctness of the advocate’s position by showing that the writer has diligently and carefully researched the legal issues and is thoroughly acquainted with the record in the case. The writer should also consider the court’s heavy workload and craft a brief to assist the court to review the merits of the case and the legal issues presented. A virtuous brief is clear, concise, and persuasive. It should be free from muddy arguments and dense prose. A brief should help the court resolve the legal dispute before it. First, present a straight-forward argument designed to convince the court that the result you advocate is fair, legally correct, and factually supported. Start out by honestly explaining the applicable state of the law. Discuss precedent from other circuits when there is a circuit split. Second, provide a thorough analysis. Explain all the steps in the analytical process. The brief should explain how the facts fit with the law in easy-to-follow steps that support the conclusion being advocated. The brief ought to anticipate and resolve questions that are likely to arise in the reader’s mind to minimize any doubts as to the brief’s accuracy or veracity. Third, write for clarity. Clear writing is essential to making a brief easy to read. Avoid cluttering the brief with unnecessary words. Finally, be concise. The argument should be short, uncomplicated, logical, and written in clear language that is easy to read.

Praise for Tragodía 1: Statement of Facts:

“Vanessa Place n’est pas une femme banale. Avocate à Los Angeles, critique d’art, écrivain…les photographies la montrent les bras tatoués, toute de noir vêtue comme une rockeuse. Son premier opus traduit en français (et son sixième ouvrage) : “Exposé des faits” ressemble à son auteur : il est étrange et fort. Parfois la littérature expérimentale est purifiante.”

—Stephanie Hochet

“No poetry book this year will be more disturbing – upsetting, unsettling – to read thanTragodía 1: Statement of Facts, by Vanessa Place.”

—Steven Fama, the glade of theoric ornithic hermetica

“… extremely disturbing on multiple levels …”

—Sina Queyras, Lemon Hound

“Vanessa Place, herself an appellate criminal defense attorney who specializes in sex offenders and sexually violent predators, has assembled a remarkable sequence of narratives, taken almost verbatim from court testimonies she herself reviewed: her cases are entirely “real.” But what is the “real” anyway? What is the difference between fact and the interpretation of fact? Between fact and truth? And what do these “true” stories tell us about the society we live in, and the way we apportion innocence and guilt? Telling it straight turns out to be the most mysterious—and poetic—way of telling it there is. No novelist could invent horror stories as compelling—and puzzling—as these actual case studies. Statement of Facts is a superb piece of conceptual writing.”

—Marjorie Perloff

“Just the facts, Ma’am. The only way to be more clever than Kathy Acker, it turns out, is to be less clever. Charles Reznikoff sampled the National Reporter System of appellate decisions for his verse in Testimony; Acker incorporated legal documents from In re van Geldern as part of her modified plagiarism; but Place recognizes that such documents are far more powerful left unedited. And they read, frequently, like the reticent syllogistic prose of Hemingway short stories. Reframed from the public record as literature, the results are emotionally unbearable.”

—Craig Dworkin

“Vanessa Place is a lawyer and, like Bartelby, much of her work involves scribing appellate briefs, that task of copying and editing, rendering complex lives and dirty deeds into “neutral” language to be presented before a court. That is her day job. Her poetry is an appropriation of the documents she writes during her day job, flipping her briefs after hours into literature. And like most literature, they’re chock full of high drama, pathos, horror and humanity. But unlike most literature, she hasn’t written a word of it. Or has she? Here’s where it gets interesting. She both has written them and, at the same time, she’s wholly appropriated them—rescuing them from the dreary world of court filings and bureaucracy—and, by mere reframing, turns them into what is arguably the most challenging, complex and controversial literature being written today.”

—Kenneth Goldsmith

“Statement of Facts is a powerful poem which forces us to question our own response to ‘documentary’ material and the nature and reliability of evidence. There’s also for me the way that language functions (and often lies) in response to our attempts to make sense of things and I’m grateful to Place for bringing this to my attention.”

—John Armstrong

“Statement of Facts is a book about limits and boundaries: physical, psychological, legal, literary, and conceptual. It is about speech and its transcription, and the strange distortions of language that have evolved to serve the legal system. It is about actions that leave a mark on the body and the soul.”

—Ken Gonzales-Day

“You might have supposed that the hallowed technique of cultural appropriation had exhausted itself in the wake of the Duchampian ready-made, the spend-thrift citations of Pop, Burrough’s lapidary cut-ups, or the critical twist given to all this by New York postmodernism in the 80s. But by re-presenting appellate briefs of sexual offense cases, attorney-cum-wordsmith, Vanessa Place has come up with another take on taking. Here the uncanny juggernaut of the Law collides with the excruciating strengths and fragilities of victims, voice is overwritten by context, and morality by salient indignation. In other circumstances we would take our hats off, but given her profession, she deserves a citation.”

—John Welchman

“By repurposing legal prosecution and defense documents of violent sexual crimes verbatim, Statement of Facts takes on issues too messy to benefit from further elucidation which only grow more disturbing presented in their purest case material form. For some, what Statement of Facts brings into the public square is salacious, but Place is in effect saying: ‘I move the ball out of this arena and take it into this arena’ in order to pump up the socio political volume on this legal/moral battlefield. Her definition of injustice is sweeping. Statement of Facts does not care what the reader thinks about content and in essence, Place’s relationship to content is like Oprah Winfrey’s to money. It is straightforward, and you are free to project onto it whatever you need to. However you respond to this fierce book, it is indisputable that Statement of Facts has carved out a place for itself as a touchstone of poetic push back. As Pasadena Superior Court Judge Gilbert Alston famously quipped in his dismissal of a 1986 rape case because the victim was a prostitute: ‘A whore is a whore is a whore’—Statement of Facts counters by unflinchingly reminding us ‘a rape is a rape is a rape.’”

—Kim Rosenfield

“Statement of Facts is poet/lawyer Vanessa Place’s masterful demonstration of day-for-night writing. Alternately nauseating, cold, gripping, philosophical, and relentless, this volume is an analytical portrait of a writer writing in double-time, simultaneously producing legal language caught in the trap of trying (and failing) to secure the self-evident meanings of the factual; and poetic language procedurally measuring the way facts are fundamentally also instruments of violence, building toward the legitimation of a legal edifice from which no one can escape. These descriptions of heinous sex crimes, detached from their original function as depositions, are a treatise on contingency; a discourse on the moral lenses of narrative; and an institutional critique of the aesthetics and ethics of juridical administration.”

—Simon Leung